Why We Need Smart Glasses for Hearing Assistance

It’s a familiar scene for many of us in the deaf and hard of hearing community: the crowded dinner table. Glasses clink, three conversations happen at once, and someone laughs at a joke you missed entirely. You’re there physically, but socially, you’re hovering somewhere outside the bubble, exhausted from the mental gymnastics of lipreading in dim light.

Hearing aids and cochlear implants are incredible miracles of engineering, but they have limits. They amplify sound, and modern ones are getting better at filtering noise, but they don’t always clarify speech. They can turn up the volume on the world, but they can’t always turn up the comprehension.

This is where the promise of augmented reality (AR) crashes into our reality. For the past few years, I’ve been obsessively tracking, testing, and living with a new category of device: smart glasses for hearing assistance designed to provide real-time subtitles for the real world. Read more about smart glasses for the deaf and people who need hearing assistance.

It sounds like sci-fi. You put on a pair of glasses, and suddenly, floating in your field of view, are the words being spoken to you. It’s closed captioning for real life. But the gap between the sci-fi promise and the messy reality of bluetooth protocols, microphone latency, and smartphone operating systems is where things get interesting, and sometimes frustrating.

If you are considering taking the plunge into seeing what you hear, you need to look past the flashy marketing videos. We need to talk about what it’s actually like to wear these things, how they play with your Android or iPhone, and the industry hurdles that are still being worked out.

The Core Concept: The Phone is the Brain

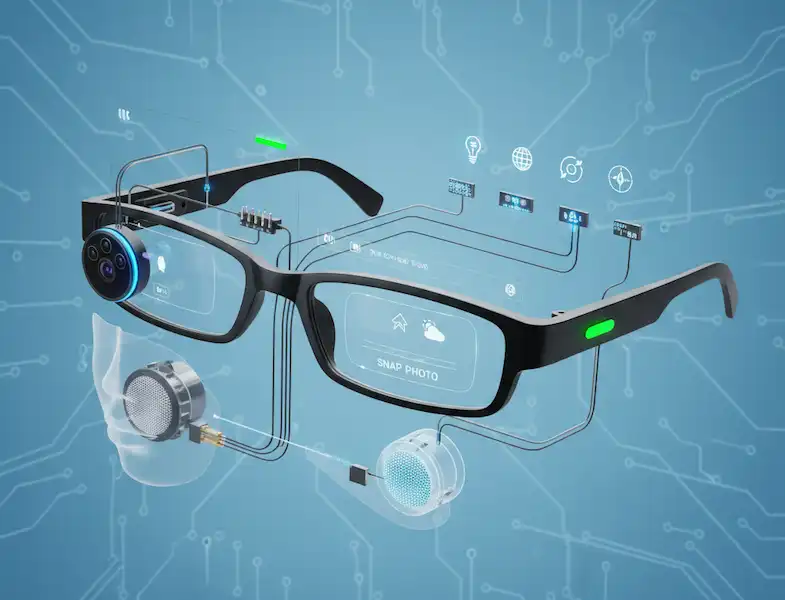

The first thing to understand is that, right now, most smart glasses for hearing assistance aren’t standalone devices. They are essentially external monitors sitting on your nose, usually tethered via a cable (though wireless is slowly arriving) to your smartphone.

The glasses themselves usually contain the display technology—often micro-OLED screens that project images onto lenses—and sometimes microphones. But the heavy lifting wasn’t happening on your face.

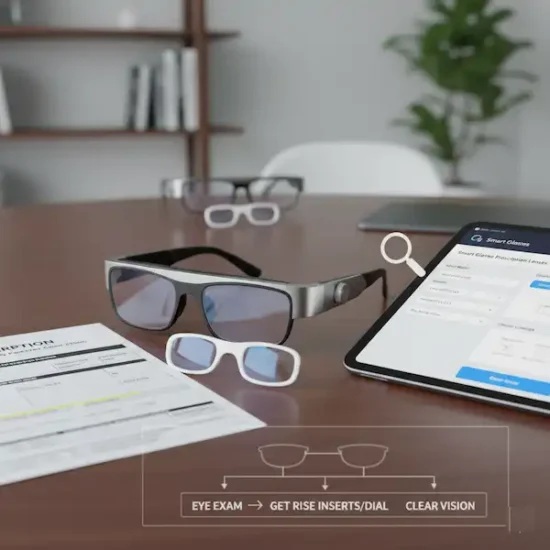

Here is the basic workflow:

- The microphones (either on the glasses or your phone) pick up speech.

- That audio is shuttled to an app on your phone.

- Your phone’s processor runs that audio through an Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) engine. This is the AI bit that turns sound into text.

- The text is fired back up the cable to the glasses and displayed as subtitles.

This whole loop needs to happen in milliseconds. If it takes too long, the captions lag behind the speaker’s lips, creating a cognitive dissonance that is almost worse than having no captions at all. This delay is called latency, and it is the arch-enemy of assistive audio tech.

The industry is currently wrestling with where that ASR processing should happen.

Cloud Processing: The audio is sent from your phone to a massive server farm (like Google’s or Microsoft’s cloud), transcribed there by powerful AI models, and sent back.

- The Good: Highly accurate, huge vocabulary.

- The Bad: Requires a strong internet connection. Latency is higher because data has to travel around the world and back. Privacy concerns about sending conversations to the cloud.

On-Device Processing: The transcription happens right on your phone’s chip using smaller, efficient AI models (like a distilled version of OpenAI’s Whisper).

- The Good: Works offline in a subway tunnel. Lower latency. Better privacy.

- The Bad: Drains your phone battery faster. Sometimes less accurate with complex jargon or heavy accents than the giant cloud models.

Right now, the best smart glasses for hearing assistance usually offer a hybrid approach, defaulting to on-device for speed but offering cloud backup when Wi-Fi is available.

The Android Experience: Open but Chaotic

If you are deep in the Android ecosystem, you have more flexibility, but also more potential headaches. Android has historically been more permissive about allowing apps to access audio streams.

For developers creating subtitling software for smart glasses, Android is often the playground of choice. It allows for things like “audio loopback,” meaning an app can capture internal audio from the device itself. Why does this matter?

Imagine you are watching a YouTube video on your phone while wearing smart glasses for hearing assistance. On Android, the captioning app can easily grab that YouTube audio directly internally and project the captions onto your glasses without needing the physical microphone to “hear” the phone’s speaker. It’s cleaner and faster.

However, Android’s fragmentation is a real issue. A Samsung phone handles Bluetooth audio routing differently than a Pixel, which handles it differently than a Motorola. I’ve tried setups that worked flawlessly on a Pixel 7 Pro but turned into a buggy mess of disconnections on an older Samsung Note.

Furthermore, Android’s aggressive battery optimization features often try to kill the smart glasses for hearing assistance captioning app in the background, causing the subtitles to suddenly vanish mid-sentence. You have to dive deep into settings to “whitelist” these apps to ensure they stay alive.

The iPhone (iOS) Experience: Walled Garden Stability

Using an iPhone with smart glasses for hearing assistance is a very different vibe. Apple keeps a tight leash on how apps can access the microphone and internal audio.

For years, this made real-time captioning apps difficult on iOS. An app generally couldn’t listen to the microphone while another app was playing audio. Apple has loosened up over time, but the restrictions are still there.

Where iOS shines is stability and the “Live Listen” feature. iOS has robust accessibility frameworks built-in. MFi (Made for iPhone) hearing devices have deep integration into the OS.

For smart glasses, the connection on an iPhone tends to be rock-solid once established. You rarely deal with the random app-killing that plagues Android. However, you often run into limitations with internal audio captioning. If you get a phone call, the captioning app might be booted off the microphone access so the phone app can take over.

Developers on iOS often have to use clever workarounds to keep the microphone active in the background to ensure continuous captioning. It usually works, but it feels like the OS is occasionally fighting the goal of the hardware.

The Elephant in the Room: Looking Like a Cyborg

We have to talk about the social aspect. I remember the first time I wore a pair of Nreal (now Xreal) glasses running captioning software into a coffee shop. These aren’t subtle like Meta Ray-Bans. They are thicker, strangely reflective, and often have a cable running down to your pocket.

I felt incredibly self-conscious. It felt like everyone was staring. And to be honest, some were.

Wearing smart glasses for hearing assistance changes the social dynamic. When you are talking to someone and suddenly your eyes drift slightly up and to the right to read what they just said, they notice. It breaks eye contact.

You have to develop a preamble: “Hey, I’m deaf/hard of hearing, these glasses put subtitles on what you’re saying so I can catch everything.”

Usually, people think it’s cool. It turns an awkward disability accommodation into a neat tech demo. But it’s exhausting to have to explain your face gear to every cashier and barista.

There is also the “glasshole” factor—a hangover from the Google Glass days. People worry you are recording them. Most current assistive glasses don’t even have cameras (to keep weight and cost down), focusing only on displays. But the public doesn’t know that. You have to manage that perception.

Real-World Scenarios: Where They Shine and Fail

After countless hours of wearing these things, patterns emerge in where they actually help smart glasses for hearing assistance versus where they are just dead weight.

The Lecture Hall / Presentation (The Sweet Spot): This is where smart glasses for hearing assistance are absolute game-changers. If there is one clear speaker, perhaps wearing a microphone, the accuracy is phenomenal. I sat through a dense technical conference keynote recently. Usually, I’d catch about 60% and be exhausted. With the glasses, I caught roughly 95%. I could relax and actually absorb the information instead of just trying to decrypt sounds.

The Quiet Living Room: Watching TV with my partner used to involve finding a volume compromise where I could hear, and they weren’t being blasted out of the room. Now, I wear the glasses. They get normal volume; I get subtitles right over the screen. It’s restored a sense of domestic normalcy.

The Noisy Restaurant (The Ultimate Challenge): This is where the tech currently stumbles. The human brain is incredible at “the cocktail party effect”—isolating one voice among many. ASR engines are still terrible at this.

In a loud bar, the glasses tend to “hallucinate.” The AI tries frantically to make sense of the clattering plates, background music, and four competing conversations. The result is often a stream of gibberish streaming across your eyes.

Industry insiders know this is the next great hurdle. It’s not about better displays anymore; it’s about better beamforming microphones and AI that can be trained to lock onto a specific speaker’s voice profile and ignore the rest. Some apps are trying to use the phone’s directional microphones to point at the person you want to hear, but it’s awkward to point your phone at someone like a reporter’s mic just to have dinner.

The Battery Anxiety is Real

Because the phone is doing the heavy processing, smart glasses for hearing assistance suck battery life like a smoothie.

Running an on-device speech recognition model, powering the display output over USB-C, and keeping the screen on is a massive power draw. On my Pixel, a two-hour dinner using live captions can easily chew through 40% to 50% of my battery.

If you rely on your phone for navigation, work email, and emergencies, this is a major problem. You cannot leave the house without a hefty power bank if you plan on using the glasses for any significant length of time.

The glasses themselves, if they have internal batteries (some do, some draw solely from the phone), add another layer of charging anxiety.

The Future: What We Are Waiting For

The current generation of smart glasses for hearing assistance are brilliant, flawed prototypes of the future. They prove the concept works, but the execution is still clunky.

We are waiting for a few key developments that industry watchers know are in the pipeline.

First, Bluetooth LE Audio and Auracast. This is the new Bluetooth standard designed specifically for audio. It offers lower latency and higher quality with less power consumption. Crucially, it allows for broadcasting audio to multiple devices. Imagine walking into a lecture hall, and your glasses automatically pick up the “Auracast” stream from the speaker’s microphone, feeding you perfect, direct-source captions without your phone’s mic having to struggle with room noise. The Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) has been vocal about the potential of these technologies.

Second, better form factors. We need these to look like normal glasses. The technology needs to shrink. We need waveguide displays that are totally transparent when not lit up, and frames that don’t scream “gadget.”

Third, multimodal AI. Right now, the glasses only process audio. The future is AI that uses cameras on the glasses (privacy concerns notwithstanding) to read lips to improve accuracy in noise, or to identify who is speaking in a group and color-code their subtitles.

Conclusion

Living with smart glasses for hearing assistance right now is like using the early internet in the 90s. It’s slow, it disconnects, it looks weird, and sometimes it just plain fails. But when the connection hits, and the data flows, you get a glimpse of a future that is profoundly better.

For those of us with hearing loss, the ability to simply see what someone is saying re-opens doors that we felt were closing. It reduces the agonizing mental load of constant active listening.

If you are tech-savvy, patient, and willing to tolerate the quirks of bleeding-edge hardware, these devices are worth exploring today. They aren’t a cure, but they are a incredibly powerful tool in the toolbox. For everyone else, keep a close watch on this space. The moment these things look like normal Ray-Bans and last all day, the world is going to change for us.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Do smart glasses for hearing assistance work without a smartphone? A: Generally, no. Most current accessible smart glasses are displays that rely on the computing power and internet connection of a connected smartphone to process the audio and generate the captions.

Q: Can I wear them over my prescription glasses? A: This depends heavily on the hardware. Some models, like the older Epson Moverio, were designed to fit over frames. Many newer, slimmer AR glasses require you to purchase separate prescription inserts that clip onto the inside of the smart lenses.+1

Q: How accurate are the subtitles? A: In quiet environments with clear speakers, accuracy can exceed 95%. However, accuracy drops significantly in noisy environments, with heavy accents, or if multiple people speak at once. It is rarely perfect, but often “good enough” to follow the context.

Q: Do these glasses also act as hearing aids? A: Mostly no. They are primarily visual aids for hearing. They do not typically amplify sound tailored to your audiogram. However, you can usually wear your standard hearing aids or cochlear implants while wearing the glasses.

Q: Are there privacy issues with recording audio for captions? A: Yes, it’s a valid concern. If you use cloud-based processing, audio is briefly sent to a server. If you use on-device processing, the audio stays on your phone. It is always best practice to inform people you are using captioning technology during a private conversation.

Additional Helpful Information

Read about using smart glasses for people with low vision – Smart Glasses for Low Vision

Authoritative Links

Advocacy & Information Organizations

- Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) – Technology: The leading US organization for people with hearing loss. Their technology section provides updates on the latest assistive listening systems and Bluetooth standards like Auracast.

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD): A division of the NIH that provides scientifically-vetted information on assistive devices, from hearing aids to emerging speech-to-text systems.

- RNID (Royal National Institute for Deaf People): A UK-based charity that offers extensive guides on how modern products—including smart glasses and mobile apps—integrate into a deaf person’s daily life.

Academic Research & Technical Studies

- Comparison of AR Glasses for Assistive Communication (via PubMed Central): A clinical study that evaluates specific hardware like Xreal, Epson Moverio, and Even Realities for their ability to provide accurate real-time transcription.

- Evaluating Usability of Real-Time AR Audio Captioning (University of Toronto): This research paper dives deep into “latency” (delay), explaining why even a 3-second lag can significantly disrupt a conversation for a deaf user.

- Factors Influencing the Use of AR Glasses as Hearing Aids (MDPI): A sociotechnical analysis of why people choose smart glasses over traditional hearing aids, highlighting the reduced social stigma of eyewear.

Community Insights & Reviews

- The Limping Chicken – Smart Glasses Review: One of the world’s most popular deaf blogs. This specific article provides a first-hand account of wearing captioning glasses in a cinema setting.

- Nagish – Technology Review of Smart Glasses: An in-depth breakdown of current market leaders like XRAI and Nreal from an accessibility-first perspective.